Recent Advances

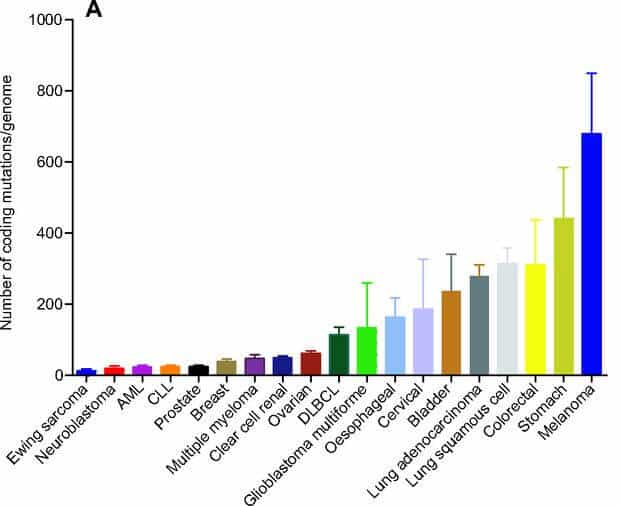

Thanks to recent breakthroughs in immunotherapy, some patients with a highly mutated cancer (up to thousands of mutations) can now gain several years of life, and even sometimes undergo complete remission, while they would have been condemned just 2 or 3 years ago.

However, the majority of patients cannot benefit from these medical advances because their tumor cell mutation rate is too low to trigger an immune activation, necessary for the rejection of their(s) tumor(s).

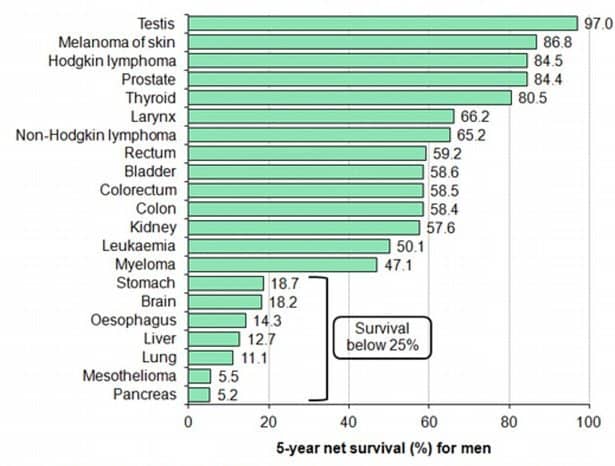

Cancer: Quick facts and figures

Cancer is the second leading cause of death globally and accounted for about 9 million deaths last year, a number expected to rise by 70% over the next 20 years. Globally cancer is responsible for 1 in 6 deaths, and its total annual cost is estimated at about 1.2 trillion dollars. Experts estimate that in Europe and North America, 1 in 2 people will develop cancer at some point in their life.

Overall, those responsible for the highest numbers of deaths yearly are lung (1.7 million), liver (788K), colorectal (774K), stomach (754K) and breast (571K) cancers.

Immunotherapy and checkpoint inhibitors

Overcoming immune evasion mechanisms

One of the hallmarks of every cancer is its ability to progressively escape our immune surveillance through numerous complex mechanisms. Modern immunotherapy approaches in cancer treatment can be very efficient to treat patients whose immune system has been initially activated following the detection of cancer cells, and then became anergic due to immune evasion mechanisms.

In this situation, immunotherapeutic approaches such as checkpoint inhibitors can restore the immune system action against cancer cells, with an increasing efficacy. Therapeutic antibodies anti-CTLA4 (ipilimumab), anti-PD1 (nivolumab, pembrolizumab) and anti-PDL1 (atezolizumab) are now routinely-used checkpoint inhibitors that have proven their efficacy.

Only certain patients can respond

Close to 70% of cancers induce no (or very weak) spontaneous immune activation due to a low number of mutations expressed by cancer cells. Those poorly mutated cells are indeed too similar to healthy cells to be recognized by the immune system.

Since immunotherapy approaches such as checkpoint inhibitors are not suited for these patients, it is appropriate to opt for a therapy that will activate the immune system by redirecting immune cells towards the tumor site.

Targeted therapies

Targeting aberrant cells

Antibody-targeted therapies have a huge potential to help the immune system detect and kill cancer cells.

As of today, these anti-cancer antibodies on the market or under clinical development are engineered to bind a cancer target present in as many patients as possible. These targets are usually natural proteins that are overexpressed or altered due to a mutation in the tumor genome.

What mutations are actionable ?

A major limit to current targeted therapies is that the vast majority of mutations present in a tumor are not actionable, either because they are patient-specific or because there is no therapy targeting them yet.

As a result oncologists rarely manage to identify an actionable mutation in patients with a poorly-mutated cancer. Besides, when a patient presents with an actionable mutation, this mutation is often not sufficiently represented in the tumor to enable an efficient treatment.

In such circumstances, the best approach is to develop more personalized treatments able to specifically target mutations that have a real clinical benefit for each patient.